Guest post published on Nottingham University’s China Policy Institute blog.

Digital methods have revolutionized many aspects of the study of pre-modern Chinese literature, from the simple but transformative ability to perform full-text searches and automated concordancing, through to the application of sophisticated statistical techniques that would be entirely impractical without the aid of a computer. While the methods themselves have evolved significantly – and continue to do so – one of the most fundamental prerequisites to almost all digital studies of Chinese literature remains access to reliable digital editions of these texts themselves.

Since its origins in 2005 as an online search tool for a small number of classical Chinese texts, the Chinese Text Project has grown to become one of the largest and most widely used digital libraries of pre-modern Chinese writing, containing tens of thousands of transmitted texts dating from the Warring States through to the late Qing and republican period, while also serving as a platform for the application of digital methods to the study of pre-modern Chinese literature. Unlike most digital libraries and full-text databases, users of the site are not passive consumers of its materials, but instead active curators through whose work it is maintained and developed – and increasingly, not all users of the library are human.

Digitization piece by piece

As libraries have increasingly come to recognize the value of digitizing historical works in their holdings, many institutions with significant collections of Chinese materials have committed themselves to large-scale scanning projects, often making the resulting images freely available over the internet. While an enormously positive development in itself, for many scholarly use cases this represents only the first step towards adequate digitization of these works. Scanned images of the pages of a book make its contents accessible in seconds rather than requiring a time-consuming visit to a physical library, but without a machine-readable transcription of the contents of each page, the reader must still navigate through the material one page at a time – finding a particular word or phrase in the work, for example, remains a time consuming task.

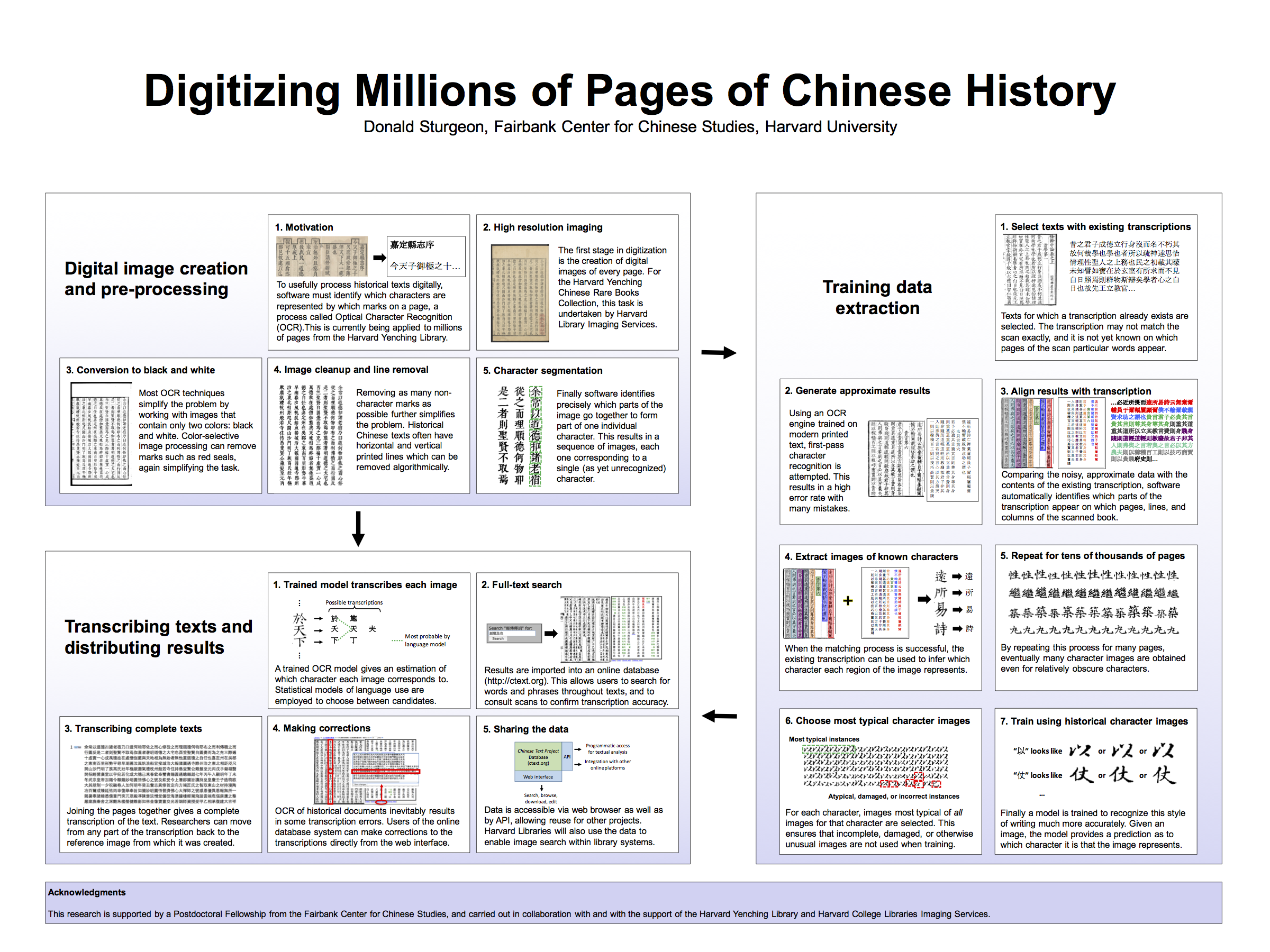

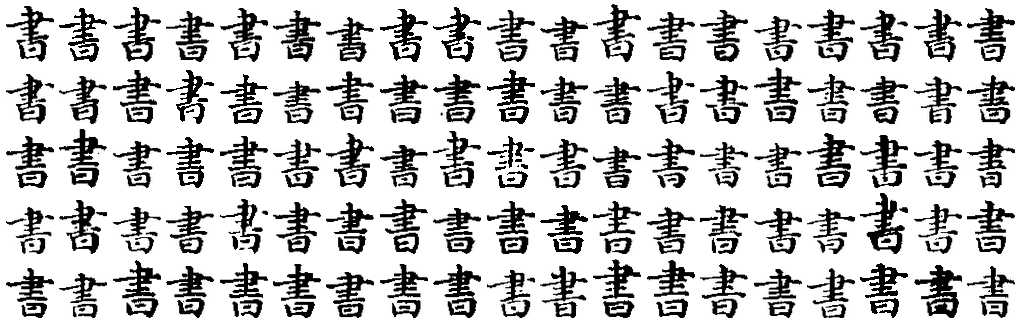

While Optical Character Recognition (OCR) – the process of automatically transforming an image containing text into digitally manipulable characters – can produce results of sufficient accuracy to be useful for full-text search, OCR inevitably introduces a significant number of transcription errors which can only be corrected by manual effort, particularly when applied to historical materials which may be handwritten, damaged, and faded. Proofreading the entire body of material potentially available – likely amounting to hundreds of millions of pages – would be prohibitively expensive, but omitting the proofreading step limits the utility of the data.

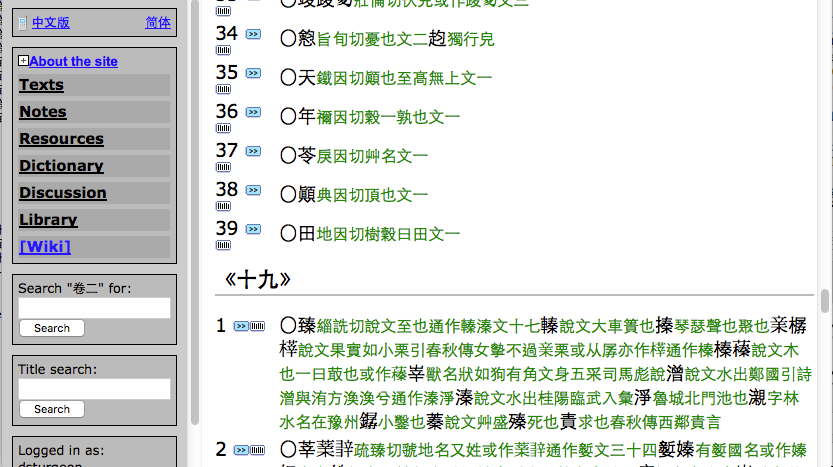

Variation in instances of the character “書” in texts from the Siku Quanshu. OCR software must correctly identify all of these instances as corresponding to the same abstract character – a challenging task for a computer.

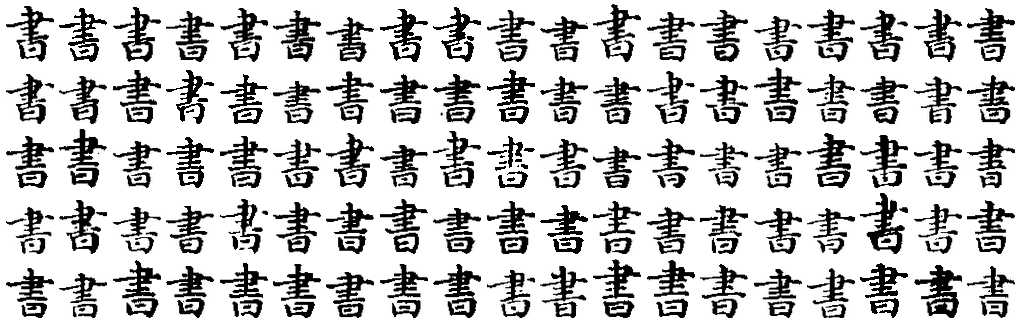

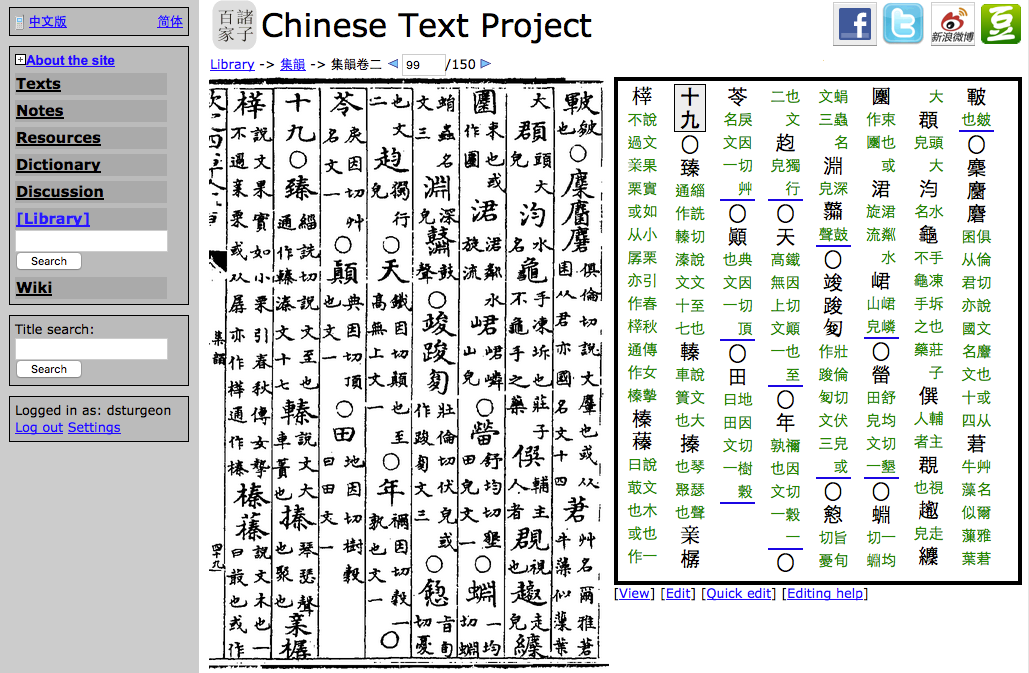

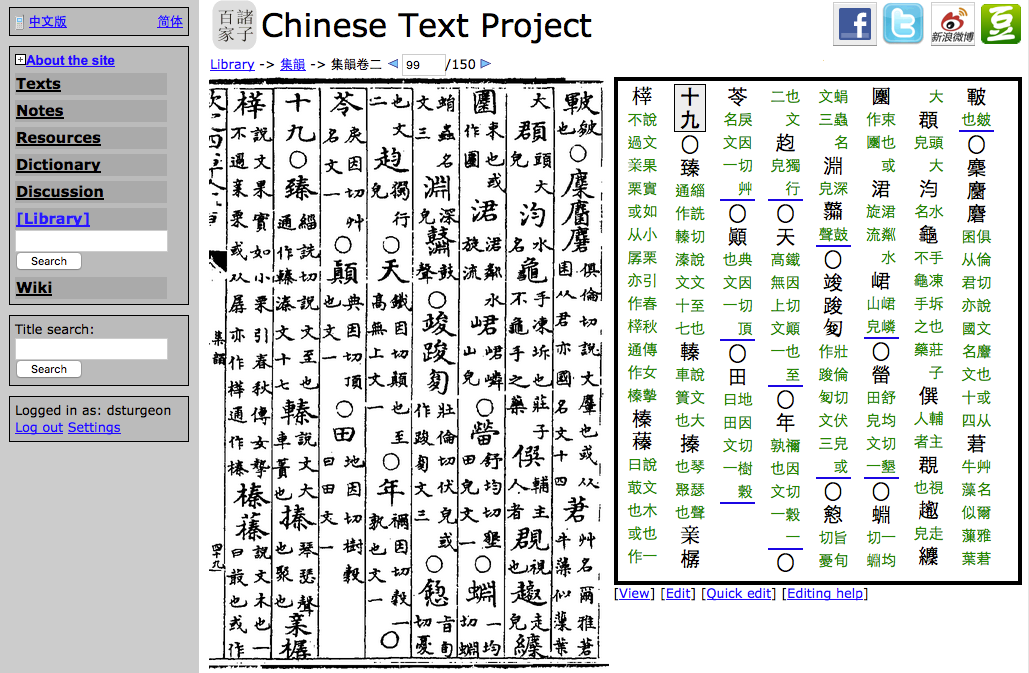

In an attempt to address this problem, the Chinese Text Project has developed a hybrid system, in which uncorrected OCR results are imported directly into a database system providing full-text search of the source images and assembling the contents of the scanned images of pages into complete textual transcriptions, while also providing an integrated mechanism for users to directly correct the data. Like articles in Wikipedia, the contents of any transcription can be edited directly by any user; unlike Wikipedia, there is always a clear standard against which edits can easily be checked for correctness: the images of the source documents themselves. Proofread texts and uncorrected OCR texts are presented and manipulated in an identical manner within the database, with full-text search and image search available for both – the only distinction being that users are alerted to the possibility of errors in those texts still requiring editing. Volunteers located around the world correct mistakes and add modern punctuation to the texts as time allows and according to their own interests – typically hundreds of corrections are made each day.

Left: A scanned page of text with a transcription created using OCR and subsequently corrected by ctext.org users.

Right: The same data automatically assembled into a transcription of the entire text.

Library cards for machines: Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)

As digital libraries grow in size and scope, they also present increasingly valuable opportunities for research using novel methods including text mining, distant reading and other techniques that are often grouped under the label “digital humanities”. At the same time, what can in practice be achieved with individual projects and their associated tools and materials is frequently limited by the particular use cases envisioned by their creators when these resources were first designed and implemented. Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) – standardized mechanisms through which independently developed pieces of computer software are able to share data and functionality in real time – provide one approach to greatly increasing the flexibility and thus utility of such projects.

With these goals in mind, the Chinese Text Project has recently published its own API, which provides machine-readable export of data from any of the texts and editions in its collection, together with a mechanism to make external tools and resources directly accessible through its user interface in the form of user-installable “plugins”. While many of these have already been created – such as those for the MARKUS textual markup platform as well as a range of online Chinese dictionaries – the true value of such APIs lies in their flexibility, in particular their ability to be adapted to new resources and new use cases without requiring additional coordination or development work, often leading to their successful application to use cases quite unrelated to those for which they were first created.

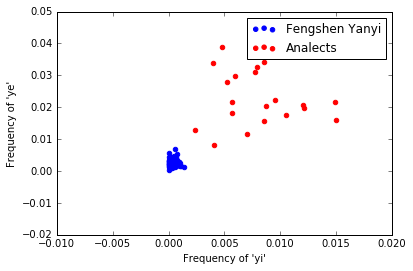

While the Chinese Text Project API was developed primarily with the goal of facilitating online collaboration, it is now also being used to facilitate digital humanities teaching and research. In the spring semester of 2016, graduate students at Harvard University’s Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations made extensive use of the API as part of the course Digital Methods for Chinese Studies, which introduced students with backgrounds in Chinese history and literature to practical programming and digital humanities techniques. By making use of the API, it was possible for students to obtain digital copies of precisely the texts they needed in exactly the format they required without the significant additional effort this would normally entail. Rather than working with set example texts for which data had been pre-compiled into the required format or spending classroom time dealing with uninteresting methods of data preparation, the API made it possible for students to directly access the texts most relevant to their own work in a consistent format with no additional work. For the same reasons of consistency, programs written to perform a given set of operations on one text could immediately be applied to any other text from the tens of thousands available through the API.

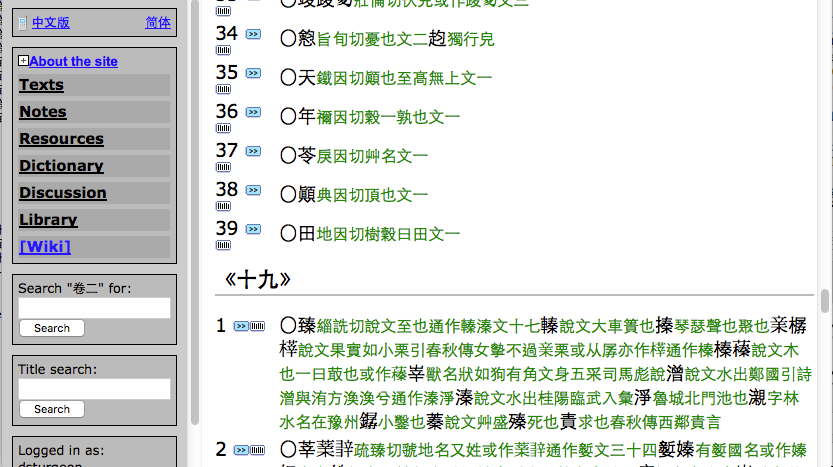

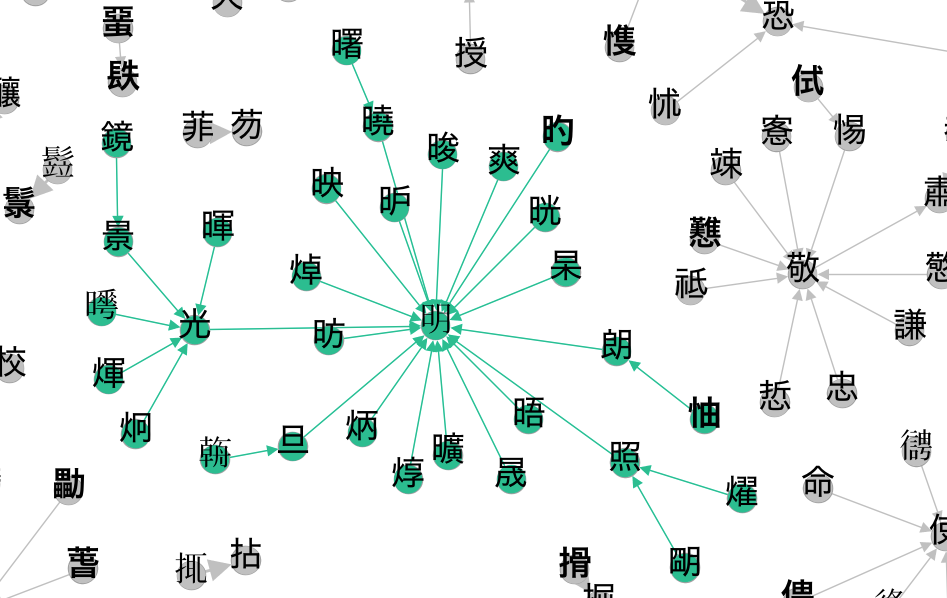

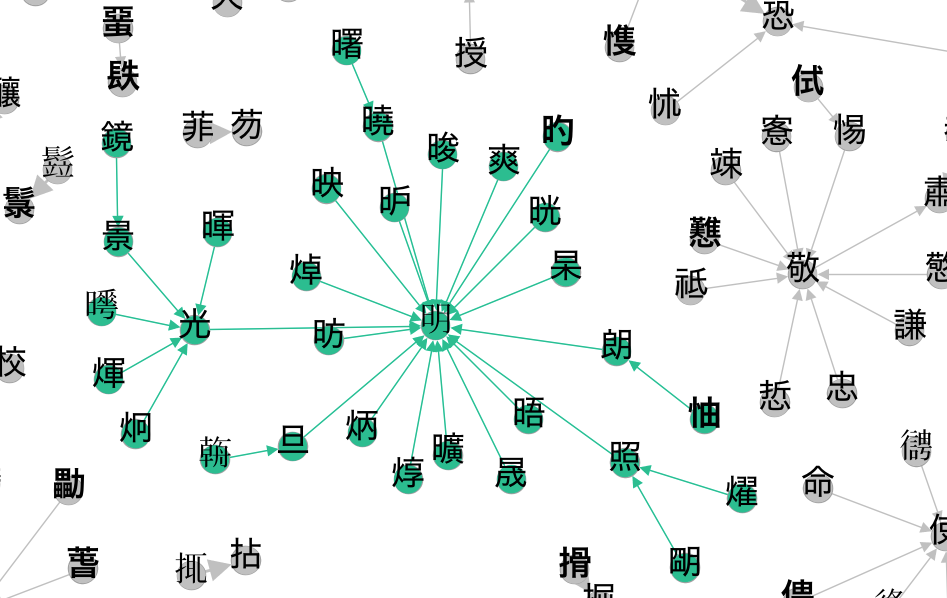

Part of a network graph representing single-character explanatory glosses given in the early character dictionary the Shuowen jiezi. Arrows indicate direction of explanation.

Conclusion

The application of digital techniques developed in other domains to humanities questions – in this case, of crowdsourcing and APIs to the simple but fundamental question “What does the text actually say?” – is characteristic of the emerging field of digital humanities. Collaboration – facilitated in this case by these same techniques – often plays an important role in such projects, due to the enormous amounts of data available, the scalability of digital techniques in comparison to individual manual effort, and the power of digital methods to help make sense of a volume of material larger than any individual could plausibly analyze by hand.

Donald Sturgeon is Postdoctoral Fellow in Chinese Digital Humanities and Social Sciences at Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, and editor of the Chinese Text Project.